In Hogg v. Blackbeard Operating,[1] the El Paso Court of Appeals was tasked with interpreting whether the granting language in an assignment was broad enough to cover a lease that was not specifically named in the exhibit. The trial court found that the lease in question was assigned, and Hogg appealed. The simplified facts are as follows.

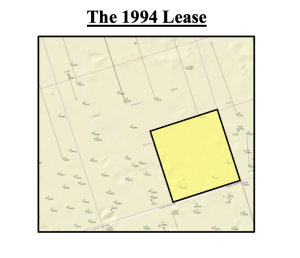

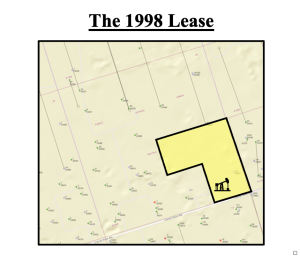

In 1994, Betty, George, and Mark Hogg (“the Hoggs”) executed an oil and gas lease to Three B Oil Company (“Three B”) covering 160.00 acres of land, being all of the SE/4 of Section 24, Block B-10, PSL, Winkler County, Texas (the “1994 Lease”). In 1998, the Hoggs executed a new lease to Three B covering 120.00 of the same acres of land, being the SE/4 SE/4 and the N/2 of said Section 24 (the “1998 Lease”).[2] The Hoggs’ interest was subsequently conveyed to Mark S. Hogg, LLC (“Hogg”).

| The 1994 Lease | The 1998 Lease |

|

|

Three B drilled the F.H. Hogg #2 Well on the 1998 Lease. In 2005, Three B and others executed an assignment (the “2005 Assignment”) to Stanolind Oil Corporation (“Stanolind”). As a result of a series of mesne conveyances, Blackbeard Operating, LLC (“Blackbeard”) eventually succeeded in Stanolind’s interest.[3]

The 2005 Assignment included a broad granting clause, as well as a reference to “Exhibit A” and “Exhibit A-1” attached thereto. While Exhibit A listed the 1994 Lease, it did not specifically tabulate the 1998 Lease.[4] However, “Exhibit A-1” named the F.H. Hogg #2 Well, which the parties agreed had been drilled on the 1998 Lease.

In 2019, Blackbeard filed suit, seeking a judicial determination that the 1998 Lease was conveyed in the Assignment. Hogg answered alleging that because the 1998 Lease was omitted from Exhibit A, no interest passed. Further, Hogg argued Exhibit A-1 did not convey any interest because it “merely identified the name of a unit” and not the 1998 Lease itself.[5] The 2005 Assignment itself purported to convey the “Assets”, which were defined in the relevant part as:

Subparagraph A. All of those interests that are set forth on Exhibit “A” that is attached hereto and made a part hereof for all purposes in the oil and gas leases… (collectively, the “Leases”); and all other properties and interests of the Assignor, including, but not limited to, any and all interests of the Seller in those Leases, together with each and every kind and character of right, title, claim, and interest in and to any and all lands, including any surface interests and the improvements located thereon, and the lands covered by the Leases . . . including, but not limited to, those lands that are described on the Exhibit “A” that is attached hereto and made a part hereof (collectively, the “Lands”) . . .

Subparagraph C. All leasehold interest in or to any pools or units that include any Lands or all or a part of any Leases or include any Wells, including, but not limited to, those pools or units shown on Exhibit “A-1” (the “Units”), and including, but not limited to, all leasehold interests attributable to the interests set forth in Exhibit “A” as to any such Unit, whether such Unit production comes from Wells located on or off of a Lease, and all tenements, hereditaments, and appurtenances belonging to the Leases and Units . . .

. . . Despite the varying degrees of ownership and interest in the Assets, all of the members of the Assignor group have joined in the execution of this Assignment, not for the purpose of clouding title, but for purposes of confirming that the Assignor conveys to the Assignee all of the right, title, and interest in the Assets that any and all of the members of the Assignor group may own, regardless of the quantum of interest owned by each member of the Assignor in each Asset. Each member of the Assignor group joins in the execution of this Assignment in order to confirm that any working interest in any of the Assets of any member of that group vests in the Assignee.[6]

Accordingly, the Court applied a standard “four-corners” approach to discern the intent of the parties in the 2005 Assignment.[7] Within the four-corners construct, deeds are construed “to confer upon the grantee the greatest estate that the terms of the instrument will permit.”[8] Furthermore, the Court noted that the greatest estate the terms of an instrument permits differs in concept from the greatest estate possible, and a deed will pass whatever interest the grantor has unless it shows a clear intention of granting a lesser estate.[9]

First, the Court noted that the 2005 Assignment is unambiguous and uses clear, plain language to convey broad interests in the properties described, including detailed definitions where necessary. At issue “is simply the interpretation of the language used.”[10] The Court found that, when read together, the various provisions of the 2005 Assignment make clear that the Assignors intended to transfer all of their interests in the “Assets” described. In determining whether Three B’s interest in the 1998 Lease was one of these “Assets,” the Court rejected Hogg’s argument that the non-inclusion of the 1998 Lease in Exhibit A precluded any interest from transferring. Instead, the Court agreed with Blackbeard that the 2005 Assignment conveyed not only the described leases but the Seller’s interest in the lands covered by the leases.[11]

Per the Court, nothing in the 2005 Assignment or its Exhibit A precluded another lease interest from being conveyed by some additional provision beyond the mere inclusion on Exhibit A. In addition to conveying all the interest in the specific Leases described in Exhibit A, Subparagraph A of the 2005 Assignment included an even broader grant of all of the Assignor’s interests in the lands covered by those Leases. The 1994 Lease covered the entire SE/4 of Section 24 (160.00 acres), and the definition of “Lands” in Subparagraph A thus included the Assignor’s interest in those all of those 160.00 acres. The fact that the omitted 1998 Lease covered a lesser 120.00 acres did not reduce this broader definition of “Lands.” Moreover, Exhibit A specifically referenced “[t]he SE/4 of Section 24, Block B-10, PSL Survey, limited in depth from the surface to 6,300 feet beneath the surface of the earth.”[12]

After determining the 2005 Assignment’s definition of “Lands” includes the 120 acres covered under the 1998 Lease, the Court turned its attention to Subparagraph C. Subparagraph C conveyed “[a]ll leasehold interest in or to any pools or units that include any Lands. . .including, but not limited to, those pools or units shown on Exhibit ‘A-1.” As stated above, Exhibit A-1 clearly identified the F.H. Hogg #2 Well, which the parties agreed was drilled under the 1998 Lease. Further, the Court found the 2005 Assignment conveyed to Stanolind all of Three B’s interest in the 1998 Lease because Subsection C’s plain terms convey “[a]ll leasehold interest” in the F.H. Hogg #2 Well, and to “confer upon the grantee the greatest estate that the terms of the instrument will permit,”.[13]

The tension between language conveying an interest in “lands” versus the presence or omission of certain leases from an assignment’s exhibit is a common issue confronting land and legal practitioners. If an assignment omit a particular lease but conveys all the rights, title, and interests of an Assignor in certain “lands”, it may create the type of “blanket” conveyance language found by the Blackbeard Court. Although not specified in the facts, it is possible in this case that the 1994 Lease had expired, and the expired lease was inadvertently listed in Exhibit A in place of the active 1998 Lease. Regardless of which lease was active, the 2005 Assignment was found to convey whatever interest the Assignor owned in the SE/4 of Section 24. As always, these types of “leases” versus “lands” inquiries warrant close scrutiny of the language of the conveyance itself.

[1] 2022 Tex. App. LEXIS 8501 (El Paso November 17, 2022, no pet.)

[2] Id. at 1.

[3] Id. at 1, 3.

[4] Id. at 2.

[5] Id. at 4.

[6] Id. at 8-14.

[7] See Piranha Partners v. Neuhoff, 596 S.W.3d 740, 743 (Tex. 2020); see also Luckel v. White, 819 S.W.2d 459, 461 (Tex. 1991).

[8] Piranha Partners, 596 S.W.3d at 747.

[9] Id. at 747-48.

[10] Hogg, 2022 Tex. App. LEXIS 8501, at 13.

[11] Id. at 15.

[12] Id. at 15-16.

[13] Id. at 16-1

Brad represents clients in connection with upstream energy transactions, complex mineral titles, pooling issues, lease analysis, joint operating agreements, surface use issues, title curative and general oil and gas business matters.

- Brad Gibbshttps://oglawyers.com/author/dbgibbs/

- Brad Gibbshttps://oglawyers.com/author/dbgibbs/

- Brad Gibbshttps://oglawyers.com/author/dbgibbs/

- Brad Gibbshttps://oglawyers.com/author/dbgibbs/

Share via: